Volume: 9, Issue: 2

30/09/2017

30/09/2017

Examining Finland’s Education Reform and its Implications for the United States

Robert McAbee1

KEYWORDS: United States, Finland, education reforms, PISA, OECD, students’ assessments, funding, science, math, reading

ABSTRACT: Finland consistently ranks at the top of the Program for International Student Assessments (PISA) reports. The United States spends more per student than Finland, but ranks in either the middle or below average for PISA rankings of student achievement in science, math, and reading. Both countries have sought to improve their systems for educating children and young adults. This paper examines the different paths taken by the United States and Finland with regards to education reform. What have been the motivating factors for education reform in the United States? How has education reform been implemented? What is the role of standardized testing in the two countries? What are the differences in Finnish education reform that account for their success? These are the questions that are briefly addressed in this paper.

Examining Finland’s Education Reform and its Implications for the United States

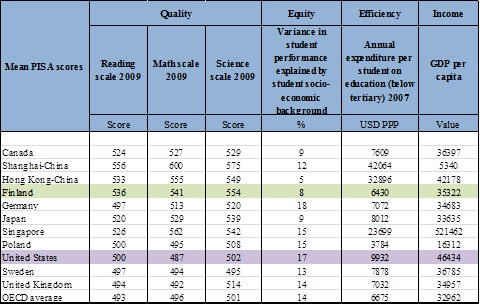

There are similarities and differences between the education systems in the United States and Finland. Throughout their post-World War II histories, reformers in both countries have called for education reform at a national level. In the United States the pushes for education reform often manifest as new federal policies or guidelines. But the ideas and policies that are endorsed at the federal level are then adopted by the states with varying levels of acceptance. In Finland there has been a slow push for an education reform, but nationally education reforms were adopted uniformly. It is important to examine the Finish school system and their reforms as Finnish students consistently score among the top countries on internationally recognized student achievement tests. The Program for International Student Assessments (PISA) reports that Finnish students are among the top countries for reading, math, and science aptitude. Finland achieved these high marks while spending less per student and also having an average income per person.

Basic Data of OECD Countries Studied in 2009

Source: OECD, PISA 2009 Database. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932366617

The main research question that I tried to answer in this paper is, what parts of the Finnish school model account for this success and how does the history of school reform in Finland compare to school reform in the United States?

Since 2000 Finland has consistently ranked at the top of 32 OECD countries in terms of education outcomes, while spending less on average than their economic counterparts. A common culture and a smaller population do not tell the story of Finland’s success, rather it is the result of steady education reform that has taken place over decades. Some of the Finnish education reforms mirror the push for education reform in the United States. But the two countries diverge when it comes to implementing their ideas of education reform.

Education reforms in the USA and Finland: A short overview

The United States education and its major reforms

In the United States education is compulsory for 12 years of schooling, although the ages students enroll and can finish schooling vary by state. Compulsory education laws in the United States go back as far as the founding of the first 13 colonies. In 1852 Massachusetts became the first state to pass a compulsory education law (Webb & Metha, 2017). Eventually each state constitution required public education to be organized and funded. Before the states began funding public education, parochial and private schools were the only schools in significant numbers. In 1917 Mississippi became the last state to pass a law mandating compulsory education. The public education laws enacted, requiring children to attend school, coincided with reform laws outlawing child labor practices. The period between the Great Depression and World War II saw a reduction in funding for state public schools. Oftentimes schools would simply be closed for long periods due to a lack of funds.

The end of World War II brought more stability to the U.S. economy and politically there was a greater focus on education. When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first satellite to orbit the Earth, the belief in United States was that the country was falling behind and the schools were partly to blame. To win this competition of nations, public schools in the United States needed to vigorously focus on math and science. This led to the Congress passing the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) (Urban & Wagoner Jr., 2013). The long-term effect of this bill was to establish the idea that public education played a key role in winning the Cold War. While individual states were responsible for funding and implementing their public school systems, the federal government would also contribute to the funding of education in order to ensure the United States remained competitive.

From the cold war to capitalism

This cry for national competitiveness was later repeated in the 1980s under the Reagan administration. In 1983, after two years of gathering data, the National Commission on Excellence in Education published the report titled A Nation at Risk. Once again the alarm was raised, because the United States was underperforming its competitors, as shown by lower test scores of U.S. students. This time the competition was not couched in terms of a military or technological race; rather U.S. school children needed the best education possible in order for the United States to compete with economic rivals like Japan, Germany, or South Korea,

The core of their economic superiority was alleged to be the educational superiority of these other nations, the evidence of which was their higher scores on international measures of educational achievement in subjects such as reading, mathematics, and science…(Webb & Metha, 2017, p. 319).

This alarm did not increase federal funding for education because Ronald Reagan was elected on a platform that claimed government spending was a problem. In spite of the furor surrounding A Nation at Risk, federal funding for education was cut. Due to tax cuts and tighter budgets, the Reagan administration did not use federal budget incentives to influence education reform nationally. Rather, there was an ideological shift that argued for giving parents and families more education choices. Specifically, families would be able to opt out of public schools and then take their portion of the state education funding and apply it to a private school. This became part of the school choice movement and is part of a political movement that argues for using state education funds for charter schools and private school vouchers.

After Reagan, the following administration under President Bush, began promoting nationalized standards for education. National standards were also endorsed by the National Governors Association. Developing national education standards was seen as a way to ensure U.S. students were prepared to compete in a global economy. During the Clinton administration, criticism of U.S. schools and the Department of Education was ratcheted back but the push for national standardized tests was embraced.

Reform at the state level

Attempts to address the shortcomings of U.S. education continued at the state level. These efforts included increasing requirements for teacher certifications and attempts to give local schools more control. In the state of Georgia teacher tenure was removed and student test scores were linked to teacher performance reviews and the ongoing support of individual public schools. These state reforms were structural attempts to achieve excellence in education, without directly changing the funding of schools.

In the United States there have also been reform attempts at the state level to address equity in funding. Not coincidentally, many of the schools identified as failing to meet the benchmarks set forth by standardized testing in the United States, also receive substantially less funding than schools that are reaching the benchmarks. This is because of how schools are funded. Within school districts, funding comes from local property taxes. School districts with more affluent populations and costlier homes will naturally have more funding. Also, when wealthier districts feel they do not have enough education funds, they can pass levies to address this. Poorer school districts have a much harder time filling in budget shortfalls that happen after state education funds are allocated. To remedy this, parents of students have sued states to ensure equity in funding. In states like New Jersey and Connecticut, plaintiffs for poorer districts won their cases and the states changed their funding model to ensure the same amount per pupil was spent in each school district (Samuels, 2016).

Education reform in the United States continues to remain in flux. Individual states have experimented with school choice and vouchers, but 90% of U.S. students still attend public schools (NCES, 2016). Across the country standardized testing is the norm although the way those results are used varies from state to state. Most states now expect school curriculums to adhere to the Common Core State Curriculum. Teacher certification happens at the state level, though organizations like the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) have pushed for higher standards of teacher training while offering certifications that are recognized in all states. Finally, in many states school funding remains an issue, as poorer schools must grapple with greater accountability and standardized tests, while working with significantly smaller budgets than their richer counterparts. More recent PISA test results show that students in the United States performed average on reading and science tests and below average for math (OECD, 2015).

Finland’s successful path in education in the past and present centuries

Finland has taken a different path towards education reform than the United States. After World War II, because of the parliamentary system, governing power in Finland was split among several parties. In 1950 most Finns left school after 6 years of education and only those living in towns or cities would have the opportunity to continue with 2 or 3 more years of middle grade education (OECD, 2010). Only one quarter of Finns had access to grammar schools, which could put a student on track to attend a university. The majority of grammar schools were privately run (OECD, 2010). After World War II, the population in Finland began shifting from mostly living on farms to living in the towns and larger cities. This increased the demand for grammar schools significantly: “Over the next decade there was explosive growth in grammar school enrolments, which grew from 34,000 to 270,000” (OECD, 2010, p. 119). A 1946 commission studied education in Finland and recommended the creation of common schools that would provide all students 8 years of education. These recommendations were not initially adopted, but ten years later the Commission on School Programs recommended compulsory education for grades 1-9 and that existing private grammar schools and public civic schools should merge into one system (OECD, 2010). These recommendations were debated, because it was not immediately agreed that all students even needed this level of education. However, in 1968, the Finnish parliament passed legislation establishing common schools for grades 1-9 (OECD, 2010). This transition happened slowly and did not become fully implemented until 1975. Upon finishing the first 9 years, students would take exams and be placed in either a university track or a vocational track for three more years. Upon finishing their 12th year, students could go on to a University, a technical college, or enter the workforce.

Teacher preparation in Finland

As part of changing the school system, Finland also addressed teacher preparation. Teacher preparation programs were consolidated at the Universities, and teachers were required to complete a master’s degree. In the United States, teachers can be certified with a bachelor’s degree and the completion of a one-year teaching program. The teaching profession in Finland is highly respected and University teaching programs receive 10 applications for each opening (OECD, 2010). Once enrolled, teacher candidates are expected to become familiar with education practices and human development. Additionally, they are required to write a research-based dissertation (OECD, 2010). When a Finnish teacher enters the profession, they are trusted and afforded a high degree of independence. Olli Luukkainen, the President of the Finnish Teachers Union stated: “Teachers in Finland are very independent. They can decide almost everything: how they will teach, what they will select from the basic (national) curriculum, when they will teach each particular topic” (OECD, 2010, p. 124). This is quite different from the United States where 44 of the 50 states have adopted the Common Core State Standards curriculum (ASCD, 2017). In Finland they have the National Curriculum Framework for Basic School, which would be considered the Finnish equivalent of the U.S. Common Core Curriculum. However, in Finland this national curriculum is considered a guideline while curriculum planning is left to the schools (Pasi, 2010. p. 6). In Finland, external standardized testing is only done on a sampling basis. As further evidence of the independence and respect given to teachers in Finland, teachers choose their own textbooks and instructional materials (OECD, 2010). In the United States school districts generally adopt textbooks and instructional materials for an entire district.

Finnish schools offering social services

One more remarkable feature of Finnish schools is that the school is leveraged to provide social services and support beyond basic education. Schools provide hot meals, dental and medical care, and mental health counseling for students and families alike (OECD, 2010). None of these services are means tested. In the United States schools provide meals to low-income students, but any school medical services are limited to screenings for vision and hearing. The Finnish school is considered part of the social safety net created by the government to help all Finnish people. In the United States schools are seen as an important part of every community, but the support of U.S. schools and the perception of what their social role should be, varies greatly.

Less emphasis on testing more emphasis on student wellbeing

One of the unique achievements of the Finnish school system is to attain quality results for students across all schools. Finnish schools are typically small enough for a teacher to know all of the students at the school. The dynamic of rich and poor schools is not present in Finland, and national standardized tests have not been implemented: “Beyond the periodic sampling assessments administered at different grades by the National Board of Education,

there is no national mechanism for monitoring the performance of schools” (OECD, 2010. p. 127). However, the Finnish schools do rely on a large amount of testing data to measure student progress, and this data is used to track students and inform teaching. Finnish schools do recognize that some children have special needs and they have created care groups to help these students. A care group can consist of the school principal, the school nurse, the special education teacher, the school psychologist, the student’s teacher, and a social worker (OECD, 2010). It is their job to identify if the areas a student is struggling in are related to learning, teaching, or social interactions. Then the team puts together a plan to support the student. These services are available to all students, because health care is provided for everyone in Finland.

The pedagogy in Finland would be described as student-centered. Students take an active role in designing their learning activities and are required to work collaboratively on projects (OECD, 2010). In the upper grades of secondary schools, Finnish students are expected to design their own program of study. Once a student creates his/her program of study, they proceed at their own pace and are not tied to a grade structure. In addition to collaborating to design their studies, Finnish students must evaluate their own learning from early in their school career. Finnish students attend school 190 days a year, but the school day is significantly shorter. This compares to the United States where the school day is over 6 hours long, and in many school districts the length of the school day is being increased. In Finland the school day is around 5 hours and teachers typically have 3-4 contact hours with their students. According to OECD figures, the average Finnish teacher instructs students about 600 hours a year, while their U.S. counterparts are responsible for 1,080 hours. Clearly, the Finnish teachers have more time to prepare lessons and decompress.

Conclusion

Finland’s results on international PISA tests show that the education model in Finland provides primary and secondary students with an excellent understanding of science, math, and literacy. There is no one factor that can be considered a silver bullet, but in Finland they have made clear choices in setting education policy for the entire country. Education reform in Finland is a process that has taken decades and started with the formalization of a national plan for education in 1968. In Finland, teacher education requires candidates to complete a Master’s degree and write a research-based thesis. The role of teachers is highly respected, and the teaching profession in Finland is very selective. Compared to the United States, the teachers in Finland actually spend less time teaching, which allows more time for lesson planning and professional development. Teachers in Finland also have a high degree of independence with regards to what they will teach.

In both the United States and Finland there is a national curriculum that outlines what students need to learn. In Finland standardized tests, based on the national curriculum, are not required or used to evaluate teachers, individual schools, or students.

In contrast, in the United States all 50 states now use standardized tests across primary and secondary school grades. In the United States no one vision for education reform has been adopted. Schools are unevenly funded, and the federal government plays a smaller role in creating education policy. Individual states still provide almost all of the funding for public education. The states also decide teacher training standards, graduation requirements, length of the school year, and how much to budget for education. Two high schools in the United States may be close geographically, but they may spend dramatically different amounts per student and have markedly different graduation rates as well.

The education comparisons between Finland and the United States are clearly between two distinctly different countries. The United States has a diverse population of over 300 million people spread across the 4th largest country in the world. Finland is a relatively homogenous country with a population of 5.5 million. However, Finland has created an education system that prioritizes the needs of students and sets high standards for teacher training. All of this is accomplished with shorter schooldays and while spending less per student. The greatest difference between education reform in the United States and Finland has been Finland’s ability to create a national policy for education reform. This has been an ongoing process that started after World War II. Finland’s education results and the choices they have made provide a model for education reform that the United States might need to consider.

References

Home | Copyright © 2026, Russian-American Education Forum