Volume: 6, Issue: 2

1/09/2014

1/09/2014

KEYWORDS: Australian universities, education.

ABSTRACT: Since 1974, the Australian tertiary sector has been convulsed by a series of major “reforms” instigated by the federal government. The main outcomes of these reforms have been the replacement of collegial institutional governance with an autocratic corporate-style management, the necessity to enrol a large cohort of scholastically weak students to increase institutional income which has been accompanied by a significant fall in academic standards, the large-scale wastage of academic staff time on a plethora of onerous and meaningless administrative tasks and paradoxically a vast increase in the number of administrators. Full-time academic positions have been steadily replaced by part-time staff who are poorly paid, poorly resourced and often undertrained. Academic staff are largely excluded from decisions that impact on their work. Degree programs are often restructured to increase student retention and graduation rates and thus, institutional income. Much of this change is justified using baseless education theory promoted by educationalists.

What is the Purpose of a University?

Public debate about the purpose of universities is a relatively recent phenomenon in Australia. As Gaita (2012) points out, universities are always vulnerable to “hijack” by the ideology of the day. Thus, while Gaita (2012) argues eloquently that the purpose of universities is to protect and nourish the “life of the mind”, the rise of free market ideology in the early 1990s and its subsequent dominance in public policy has made it is much easier to find others who believe that the role of universities is to dispense private utilitarian goods on a user-pays basis.

Universities have been with us since the 1100s, making them one of the most enduring institutions created by humans. None could argue that the benefits they have delivered to humanity are out of all proportion to their size and funding. Hitherto, their success can be attributed to the provision of an environment in which highly intelligent, imaginative and motivated individuals have the resources and freedom to pursue rational truths and educate the next generation of thinkers, untrammelled by the exploitative and inevitably destructive interventions of ephemeral cultural and political demands.

While there is a natural tension between the university and its paymaster, historical funding and governance arrangements (described below) made it possible to reach a highly workable compromise between the necessarily idealistic goals of academic work and the routine tasks of employment. It is therefore extraordinary, that over the last three decades, Australian higher education has been reduced to little more than a source of government and private revenue.

The Modern Era of the Tertiary Education in Australia

In 1957, Prime Minister Menzies accepted the Murray Report and initiated the creation of a first class university and technical college system. Universities set entry standards, charged tuition fees and had sole access to government research grants. The government implemented a generous merit-based scholarship scheme for students who could not afford the fees. Importantly, Government funding was distributed through an autonomous statutory body, which made it difficult for the government of the day to interfere unduly in university affairs.

By the 1980s, the tertiary sector was composed of technical colleges, Colleges of Advanced Education (CAEs), Institutes of Technology and Universities. The various areas of the tertiary sector were separate because they provided tuition in fundamentally different spheres of education and prepared them for fundamentally different forms of employment.

In 1974, the Whitlam (Labour) government abolished university fees. This was hailed by many as a great social advance. Others predicted disaster, as they saw it as the beginning of a move by government to gain total control over university affairs. Consistent with this prediction was the steady erosion of the responsibilities of the statutory funding body and the concomitant increase in the power of the government to control university activities.

The Hawke (Labour) government created the National Unified System (NUS) following publication of the White Paper, Higher Education: A Policy Statement, by the Department of Employment, Education and Training (DEET, 1988). The statutory basis of the NUS was the Higher Education Funding Act (1988) which gave the minister of education (John Dawkins) full control over university funding and permitted regulations to be made that forced universities to respond to the minister’s demands. Criteria for membership of the NUS were created and only members were eligible for government funding.

Tuition fees were reintroduced as part of the Dawkins “reforms”. Under the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS), students paid 50% of a government-determined subsidy that the universities received for each student enrolled in each course. A loan scheme was established for those who could not afford the fees. In Australia, student debt not expected to be repaid now stands at $6.2 billion (Grattan Institute, 2013).

The Dawkins reforms proved to be an utter disaster for Australian higher education, as misguided and often malevolent interference in university affairs by sequential governments forced the progressive deterioration of standards and funding. There is no doubt that the reforms were a politically-motivated means of reducing the electorally unpalatable level of youth unemployment by making entry to university possible for virtually anyone, irrespective of ability and promoting currently fashionable free-market ideology by converting the universities from collegially-governed institutions into top-down administered corporations. With direct and total control of funding and the authority to make any demand of the institutions in return for funding, the minister of the day was undeniably at the top!

Under the new financial arrangements, funding instantly became contingent on student numbers, thus forcing institutions to maximise income by setting ambitious enrolment targets and reduce costs by increasing the student/teacher ratio. Financial pressure was further intensified as government funding on a per-student basis reached record lows. In order to survive financially, universities had no option but to radically lower entry standards and reduce the intellectual requirements of courses, some of which became no more demanding than high school level work.

As a result of the student-number criterion set for membership of the NUS, the total number of tertiary institutions had to be reduced by about 50%. Institutions therefore had the option of merging or closing. Given that funding was now tied to student numbers and that per-student funding was falling, to remain solvent, any merger required restructuring of virtually all aspects of institutional operation. As many institutions with little in common merged to avoid closure, restructuring simply produced unwieldy and largely dysfunctional organisations.

Within the tumult of such great uncertainty, positions of authority within Australian Universities were largely purged of those whose outlook was not consistent with that of the government. Conversely, those willing to do the government’s bidding were offered career advancement and access to absolute power over their “colleagues”. This essentially corrupt dynamic saw university management positions increasingly filled by self-serving individuals who had scant regard for academic standards or collegial decision-making.

It is thus unsurprising that in recent years we have seen two of our most prestigious institutions (Monash University and the University of Queensland) go to great lengths to protect a Vice Chancellor (VC) who was a serial plagiarist and another a nepotist. While both were eventually relieved of their posts on generous terms, this only occurred when the public relations damage (i.e., the threat to institutional income), resulting from extended periods of denial in contradiction of the facts became too much (needless to say, the whistle blowers lost their jobs). On the other hand, measures of workplace stress for academic staff are now about four times the national average (Winefield, Gillespie, Stough, Dua and Hapuararchchi, 2002).

By the end of the 1990s, the nature of academic work had been grossly distorted. The vast increase in the number of bureaucrats and administrators parasitised education funds while paradoxically swamping academics with pointless administrative tasks, largely associated with government and university accountability requirements. Academics routinely spend months rewriting courses and restructuring degree programs simply to make them a more marketable product. Every two or three years the sector is forced to divert vast resources to comply with major changes required by yet another ideologically driven government review. In recent years, the most significant of these changes has been the availability of government subsidies for private education providers and the full deregulation of tuition fees.

The Rise of the Educationalist

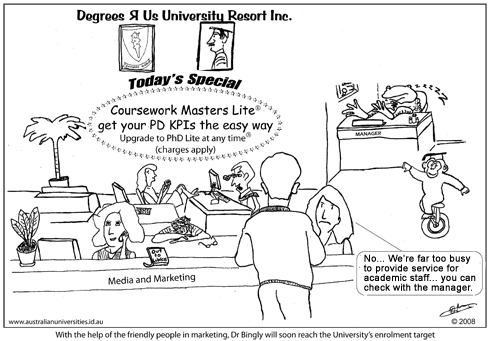

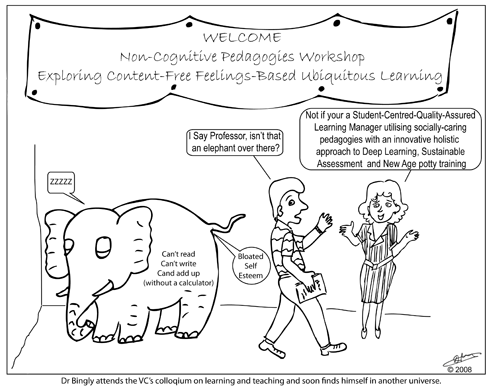

One of the most damaging outcomes of the Dawkins reforms has been the surrender of power to “educationalists” and their learning and teaching “industry”. Today educationalists occupy many highly paid academic positions in faculties and departments of education and key administrative positions within the university bureaucracy. From these positions of power they pontificate on teaching methods, student learning, forms of assessment and curriculum design without reference to anything other than the mostly ridiculous ideas (e.g. problem-based learning and constructivism (see below); sustainable assessment, action research; grounded theory; socially-caring pedagogies; blended learning; ubiquitous learning; the flipped classroom; mini MOOCs) of other educationalists.

Educationalists claim to have specialized knowledge of how to teach and how learning occurs. Yet many have little experience in university teaching and some have completed only a year or two of school teaching! Most have limited knowledge of the principles underlying the acquisition of knowledge and understanding in either the humanities or the sciences.

Typically, educationalists are also the product of soft-option humanities programs that are based on Postmodernist/(capital “T”) Theory, which has as its philosophical core, the notion that "facts" are merely convenient social constructs and that the rational pursuit of truth is therefore pointless (for a full critique see Bell, 2010). Accordingly, it is unthinkable that educationalists would make the serious effort required to become cognisant of the neurobiology of the human mind (see Snow, 2003) and its implications for teaching and learning (see Meyers, 2012, pp. 72 – 79).

Few doubt that the disgraceful standard of national literacy and numeracy (see below) is a direct consequence of the power that has accrued to educationalists over the last three decades. In their illusory world, all minds have the same potential for genius; all students are thoroughly motivated and so creative as to be able to “construct” knowledge through the exclusive use of their intellect. Successful teaching simply requires placing the student at the centre of their unique knowledge-construction process. If a student does not succeed, the failure can only lie with the teacher. This provides a compelling incentive for the teacher to disguise the failure.

Consistent with the belief in the student centred/constructivist approach is the promotion by educationalists of the belief that so-called “Problem-Based Learning” works. Problem-based learning, discovery learning, inquiry learning, experiential learning, constructivist learning (call it what you will), first appeared in the 1960s. It has been thoroughly debunked at least as many times as the name has changed (for review see Kirschner, Sweller & Clark, 2006).

Implementation of Problem-Based Learning in schools has been accompanied by a substantial reduction in both the intellectual demands of curricula and a marked decline in the use of supervised examinations. Both have been essential to obscure the obvious lack of student learning. Instead, heavy emphasis is placed on assignment work, group work, peer assessment and even (more absurdly), self-assessment. As virtually all students are allowed to progress to the next grade, irrespective of performance, there is no incentive to undertake the serious mental effort required for genuine learning.

The result of this approach is undeniable. All national and international measures of literacy and numeracy applied in Australia over the last 15 years show a steady and significant increase in the percentage of students who fail to meet the most basic standards. Even worse is the dramatic decline in the percentage of high achievers. A recent report published by the Industry Skills Councils (ISC; 2011) estimated that there are two million functionally illiterate people in the Australian work force - an utterly appalling statistic for a wealthy western democracy. When quizzed about these statistics on national radio in 2011, the President of the Australian Secondary Principals Association stated, “The issue I guess is that for many students, literacy and numeracy does not become relevant until they make their career choice . . .” and “. . . reading and writing is not very high on their [i.e. the student’s] agenda.” It is clear that responsibility for the broad-scale ignorance, which is now a facet of daily life in Australia, lies squarely with educationalists who have aided and abetted the rank exploitation of education, under the scrutiny of a succession of delinquent and incompetent politicians.

An Unhealthy Symbiosis

The primary task of university managers is to raise institutional income by continually increasing student enrolments. Indeed, managers are in constant fear that enrolment growth will stall or contract, thereby jeopardising their jobs. Continual growth has therefore necessitated the enrolment of students with ever lower scholastic ability. Throughout the 1990s, failure rates were minimised by reducing the intellectual demands and quantity of material contained in coursework and by opportunistic manipulation of pass marks. By the 2000s, many institutions were enrolling students whose scholastic ability was so poor that they could neither write a coherent sentence nor do arithmetic.

Indeed, in 2007, my former institution enrolled students in the Bachelor of Science program who were in the bottom 15% of high school leavers. By my estimate, nearly half of the first year intake was severely deficient in English comprehension, basic grammar and basic mathematics. A quantitative study at the same institution (Wiegand, 2012) suggested that with respect to mathematics, this might well have been an underestimate.

In view of these circumstances, maximising the student retention rate and thus institutional income, required a new approach. Whether by design or accident, university managers saw the opportunity to exploit the educationalist’s student centred/constructivist fantasy. Consequently, educationalists became dominant players in the preparation of learning and teaching policies. These policies put significant pressure on academic staff to adopt the pedagogical practices used in primary and secondary school education which have rendered millions of Australians functionally illiterate and innumerate.

Today, in Australia, changes to courses and degree programs that are made solely to maintain and increase the number of fee paying students are justified using the vacuous ideas peddled by educationalists. Ultimately, this translates into the justification for retaining or hiring academic staff who will give students what they want and the firing of staff who attempt to give students what they need and maintain reasonable scholastic standards. Academics are now unarguably the most vulnerable members of the education community. The upshot of this development is that management can pursue their financially motivated imperatives unhindered by arguments about academic standards.

Academic Life

For older academics, academic life today is a grotesque caricature of the pre-Dawkins era. Autonomy in any area of endeavour is non-existent, chronically under-performing students must be passed, regressive changes to teaching and assessment practices must be implemented and hours must be wasted addressing meaningless accountability requirements. Research is not a possibility for most, even though more than 90% of academics claim that this was the main reason they entered the academy (Bexley, James & Arkoudis, 2011).

It is particularly disturbing that significant pressure is now placed on academic staff to acquire a graduate qualification in education – a qualification that most consider worthless and perhaps even an embarrassment. Professor Tony Aspromourgous (2012) captured the essence of this situation when he wrote the following:

. . . virtually everyone in the system, including the academic managers, knows that the learning-and-teaching industry, as currently constituted, produces little of value for genuine university education and teaching. But while virtually everyone acknowledges this privately, publicly, almost everyone pretends that it is important and worthwhile . . . such collective dishonesty is obviously particularly corrosive in institutions that are supposed to be in the business of truth-telling . . . (p. 48)

Younger academics that postdate the Dawkins reforms know nothing else and many are no doubt content to operate within the system. In order to do this successfully, I suspect that they must treat academia as a job rather than a calling, with all that entails in terms of the relentless focus on personal advancement and the appeasement of “superiors” at the expense of collegiality, institutional loyalty and most importantly, devotion to their chosen passion.

The hallmark of modern academic life, however, is the army of part-time ghosts that do the bulk of the teaching. They are poorly paid, poorly resourced, often undertrained and hired and fired at the whim of management with scant hope of ever transitioning to a genuine academic life, if indeed such a thing exists in Australian universities.

While pockets of excellence survive, albeit under appalling conditions, it matters little whether one considers that a university should be a haven for those whose calling is the intellectual life or the driver of the knowledge economy - Australia’s universities deliver neither.

There are now so many unproductive people exploiting education, that there is little hope for positive change. They will continue to parasitise funds and make decisions that further their own interests. If positive change is to occur, it may come from the cooperative disobedience of academics themselves or, more likely and unfortunately, as the result of a catastrophe that demands the full utilization of the nation’s intellectual resources. That our geographic neighbours have avoided the educational idiocies that now plague us will most likely mean that we shall ultimately lose what little investment we hold in a nation that once showed such promise.

References

Home | Copyright © 2026, Russian-American Education Forum