Volume:9, Issue: 3

Dec. 27, 2017

Dec. 27, 2017

KEYWORDS: Vulnerable children, health determinants, inequalities, clinical services, community, partnership.

ABSTRACT: RICHER Initiative seeks to foster health equity and in particular attend to disparities in health care access that many marginalized and vulnerable children and families experience. The paper provides a brief overview of the key insights from this interprofessional clinical and research initiative and highlights the ways in intersectoral and community partnerships that contribute to improved child health and developmental outcomes.

British Columbia has the highest child poverty rate in Canada with children in Vancouver’s inner city being among the most at–risk. In 2006 we set out to develop a social pediatrics initiative that has evolved into the RICHER research to practice partnership initiative.

RICHER is the acronym for the Responsive, Intersectoral-Interdisciplinary, Child-Community, Health, Education, and Research initiative. From its outset RICHER sought to address the marked inequities in children’s health by fostering access to clinical services along the continuum of care from prevention to specialized supports and by forming partnerships and working to develop resources to address the social determinants of health.

At the outset of the initiative the team recognized that the neighborhood had a significant percentage of children who were developmentally vulnerable at school entry, and emerging longitudinal research had demonstrated that the impact of social and material adversities was cumulative over the life course. Moreover, a series of longitudinal studies and emerging neurodevelopmental research has shown that the negative impact of social and material adversity can be mitigated. The importance of engaging to improve children’s health and development was further underscored by analyses that demonstrated that when social and material adversity is left unaddressed there is a negative impact on the child that potentially incurs significant costs for not only health care systems but also for social services, education, and the criminal justice systems.

As implied in the name, RICHER clinicians work in partnership with resources of the formal healthcare, education, and municipal sector (public health, social services, school boards) and community based organizations providing services in the neighborhood (community centers, community services providers – housing, home support, child care centers, YWCA, etc.) and University based researchers to design and evaluate the impact of an innovative model of healthcare delivery on child health and developmental outcomes.

The aims of the clinical components of the RICHER program are to:

From the outset a research partnership was formed in order to:

In this paper we provide a brief overview of the key insights from this clinical and research initiative and highlight the ways in intersectoral and community partnerships contribute to improved child health and developmental outcomes.

Background to the RICHER clinical initiative

RICHER is located in the inner city and serves a population area that includes 8.5% (~10,000) of Vancouver’s children and youth. Approximately one third of the children are Indigenous while another third live in new immigrant or refugee families. And, while pediatric specialty services are only 7 kilometers away, prior to introducing RICHER, significant issues of clinical service access were documented and there were marked disparities in child health and developmental outcomes when compared with other BC communities. In particular, in this neighborhood, primary healthcare services, especially for children, were very limited.

RICHER was conceptualized as a community based, and community informed, model of clinical services provision. It was designed to complement by enhancing, enriching and extending existing clinical services. The organization of services delivery recognizes and seeks to not only provide access to clinical services but it also seeks, principally through partnerships, to mobilize resources that will allow to address the social determinants of health. Since its introduction, RICHER clinical services have been co-located in neighborhood spaces. Community input is ongoing, and all research is vetted with community.

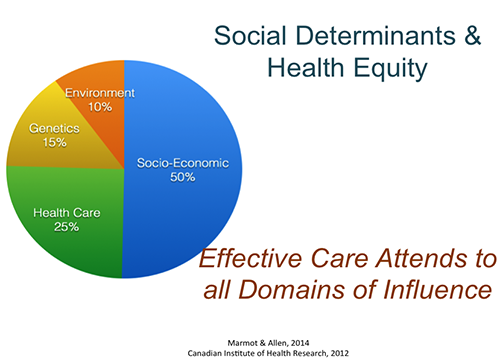

Recent population analyses underscore the value of this approach and, as Figure 1 illustrates, if we wish to foster health equity, the design and delivery of care must recognize all domains of influence on health outcomes (Marmot & Allan, 2014).

Figure 1. Social Determinants and Health Equity

Some key elements of the RICHER approach and related insights from research on it include:

The RICHER approach has fostered access to quality PHC and improved health and developmental outcomes of children in the neighborhood (Wong et al., 2012).

In addition, prior to the introduction of RICHER, provincial mapping of child developmental vulnerability at school entry was among the highest in the province (see Figure 2) with approximately 2/3 of the children being identified as developmentally vulnerable at school entry (HELP, 2008). Similar mapping, following the introduction of RICHER shows an 18% reduction in vulnerability over a time period when the provincial trend was towards increased vulnerability (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Early Developmental Indicator Map for the RICHER neighborhood. Wave 3

Figure 3. Developmental Vulnerability Map for the RICHER neighborhood. Wave 5

How then, does RICHER work?

There are a number of organizational features that distinguish RICHER from other clinical initiatives. These are captured in Figure 4.

Figure 4. RICHER Logic Model (Lynam et al., 2011)

Complementarity of services and purposeful partnerships: One feature is that RICHER draws upon existing funding models and clinical resources of the publicly funded healthcare system but the clinicians work with, and within, community based resources of both the formal and informal sector in order to integrate healthcare delivery with other services and resources.

RICHER is actively engaged in the formation of purposeful partnerships to ensure families gain access to full spectrum of resources along the continuum of clinical services and importantly to address social determinants of health. The purposeful partnerships formed to foster engagement and build trusting relationships also acted to dismantle structural barriers and foster community connectedness. For example, by partnering we were able to locate clinicians in neighborhood settings.

The purposeful partnerships also enabled us to dismantle social barriers (Lynam et al., 2010). The clinicians learned from the community and became part of the trusted networks of support. Having clinicians integrated within the community increased the likelihood that they would become familiar to families and that the families would ‘hear’ messages of support and inclusion.

Partnering enabled us to extend the range, nature and complementarity of services. Ultimately, the shared goals and engagement that resulted from partnerships benefited the children and families.

Fostering responsiveness and creating avenues of accountability. The organizational structure also created mechanisms of accountability to the community, an avenue for engagement with the clinical practice partners. These features fostered the initiative’s capacity to be responsive.

This was accomplished through the formation of a weekly ‘community table’ where clinicians, members of the community, and community organizations gather together to discuss emerging or ongoing issues that impact children’s and families’ health, as well as the approaches enhancing the responsiveness of the healthcare delivery model. Such ‘community tables’ also help to initiate a dialogue on the nature of additional resources and the search for new partners to be involved to address emergent issues. Key processes that foster responsiveness and effectiveness include organizational engagement, accountability, and trust.

How is care provided?

It is not only how the initiative is structured that contributes to the improved outcomes. It is also how care is provided that is important. Figure 5 identifies a number of dimensions of primary healthcare quality and processes of care that were most highly valued and associated with improved outcomes. The figure also illustrates characteristics of the patient-provider relationship associated with these outcomes. In particular, we learned that the clinician’s interpersonal style is positively associated with the patient empowerment (p<0.01) which is an outcome that indicates improved knowledge, capacity to activate systems, and the ability to manage child and youth health conditions (Wong et al., 2014).

Figure 5. Valued Features of Patient Provider Relationships

Conclusions

The RICHER social pediatrics initiative has sought to recognize the impact of social and material adversity on children’s health and development. It also draws upon research insights that have identified the nature of conditions and resources that are effective in mitigating the impact of such forms of adversity on children’s health and development. RICHER clinicians seek to engage with children and families in their neighborhood context, partner with neighborhood based organizations in order to create and build networks of support, to develop and mobilize resources to address the social determinants of health enabling families to provide for their children’s needs, to live safely, and thrive. As RICHER is an intersectoral partnership, clinicians are also instrumental in guiding and supporting families as they engage with other service providers in healthcare, education or social services while seeking to dismantle social and structural barriers.

Ultimately, the RICHER model is such a philosophy of services’ provision that recognizes the expertise of different sectors including the community; it seeks to respect children and their families, to uphold their rights and ultimately to ‘re-form’ systems to be responsive to the children’s and families’ needs.

References

Human Early Learning Partnership. EDI [Early Years Development Instrument] British Columbia Provincial Report, 2016. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, School of Population and Public Health; October 2016. http://www.edibc2016.ca

Kershaw, P., Irwin, L. Trafford, K. & Hertzman, C. (2005). BC Atlas of Child Development. 1st Edition. BC Human Learning Partnership. http://earlylearning.ubc.ca/media/publications/bcatlasofchilddevelopment_cd_22-01-06.pdf

Lynam, M. J., Loock, C., Scott, L. & Khan, K.B. (2008). Culture, health and inequalities: New paradigms, new practice imperatives. Journal of Research in Nursing, 13(2), 138-148.

Lynam, M.J., Loock, C., Scott, L., Wong, S., Munroe, V. & Palmer, B. (2010). Social Pediatrics: Creating organizational processes and practices to foster health care access for children ‘at risk’. Journal of Research in Nursing. Online First February 15: doi: 10,1177/17449871093605/, 1-17.

Lynam, M.J., Scott, L., Loock, C.L., Wong, S. (2011). The RICHER Social Pediatrics Model: Fostering Access and Reducing Inequities in Children’s Health. Healthcare Quarterly, 14 (3). Special Issue, 41- 56. http://www.longwoods.com/content/22576

Lynam, M.J., Grant, E. & Staden, K. (2012). Engaging With Communities to Foster Health: The Experience of inner-city children and families with learning circles. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 44 (2), 86-106.

Loock, C., Suleman, S., Lynam, J., Scott, L., & Tyler, I. (2016) Linking In & Linking Across using a RICHER Model: Social pediatrics and inter–professional practices at UBC. UBC Medical Journal, 7(2): 7-9.

Marmot, M. & Allen, J. (2014). Social Determinants of Health Equity. Editorial. American Journal of Public Health –Supplement 4, 104(54), S517-519.

Wong, S.T., Lynam, M.J., Khan, K., Scott, L. & Loock, C. (2014). The Social Pediatrics Initiative: A RICHER model of primary health care for at risk children and their families. BMC Pediatrics, 12:158 (doi - October 4, 2012).

1 Judith Lynam, PhD, RN, Professor, School of Nursing, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Dr. Christine Loock, MD, Pediatrician & Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Canada, Specialist Lead; Lorine Scott, Nurse Practitioner (Family), Primary Care Lead. In ongoing partnership with Kate Hodgson, Ray Cam Community Co-operative, Network of Inner City Services Society; Dr. Dzung Vo and Dr. Eva Moore, RICHER Pediatricians; Gwyneth MacIntosh, Kristine Pikksalu, Clea Bland, and Denise Hanson, RICHER Nurse Practitioners.

Home | Copyright © 2026, Russian-American Education Forum