Volume:5, Issue: 1/2

May. 1, 2013

May. 1, 2013

DESCRIPTORS: Tatar education, national language, confessional education, educational principles, Russian-Tatar schools, encyclopedic knowledge, “Book on education,” precepts, moral education.

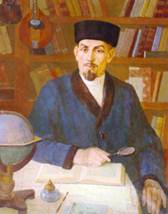

SYNOPSIS: This paper introduces the name and activities of an outstanding Tatar educator and thinker Kayum Nasyri, whose influence on the national Tatar education could be compared to the influence of Konstantin Ushinsky on Russian education. The author shows that regardless of miserable life conditions and hatred from his religious countrymen, Nasyri managed to leave such an incredible heritage that is worth many years of research and hundreds of researchers all over the world.

The end of the 19th - early 20th century is characterized by the formation of national Tatar education system, national mass media, literature and theatre, together with a new type of intellectuals striving for the unity of traditional cultural values and Tatar national development. The innovative approach that is known in history as “Jadidism” gradually evolved in the Tatar education system. The origin of this term comes from the name of a new method of teaching "Usul Jadid," and the latter became possible due to the reform of the traditional confessional education and the development of a sound method of teaching [1; 4]. Especially influential in this movement was an outstanding Tatar educator, researcher and writer Kayum Nasyri (1825 - 1902), well known to anyone who is familiar with the history and culture of the Tatar people.

The end of the 19th - early 20th century is characterized by the formation of national Tatar education system, national mass media, literature and theatre, together with a new type of intellectuals striving for the unity of traditional cultural values and Tatar national development. The innovative approach that is known in history as “Jadidism” gradually evolved in the Tatar education system. The origin of this term comes from the name of a new method of teaching "Usul Jadid," and the latter became possible due to the reform of the traditional confessional education and the development of a sound method of teaching [1; 4]. Especially influential in this movement was an outstanding Tatar educator, researcher and writer Kayum Nasyri (1825 - 1902), well known to anyone who is familiar with the history and culture of the Tatar people.

Kayum Nasyri was born on February 14th, 1825, in the village of Upper Shirdany of Sviyazhsky district in Kazan province (now Zelenodolski region of Tatarstan) in the family of an influential local theologian and master of calligraphy Gabdenasyr bin Hussein. The founder of this dynasty was a respected Birash Baba who settled on the right bank of the Volga River in the time of the Kazan Khanate. For several centuries, the descendants of the dynasty were recognized Muslim leaders, serving as village mullahs. Kayum’s grandfather, Hussein bin Al'mukhamed, was not only an imam (a Muslim leader) in the Upper Shirdany but also a teacher and a researcher. He wrote several books on Arabic grammar and syntax, used and enjoyed by numerous students from Muslim schools, called “mektebe.” His son Gabdenasir took after the father, had fundamental knowledge in different fields and a brilliant mind, and was also known as a researcher of Islam. He studied the theory of the Arabic language and was heavily engaged in making professional copies of different Oriental books. However, Gabdenasir did not become a religious leader, spending all his time and energy in the work to benefit his native village and fellow villagers. No wonder, they called him Gabdenasyr Khazret, which means "merciful" [3].

So the life style of Kayum Nasyri was largely predetermined by his family traditions and the brilliant examples of his ancestors. Kayum received his elementary education in the village school, and later, in 1855, moved to Kazan for continuous studies at the “Kasimia” Madrasah (religious school), one of the largest Muslim educational institutions of that time. The Madrasah was famous for a high level of education, mostly due to a number of highly professional and prominent teachers such as Shigabutdin Marjani, Ahmad Zaki Validi, Ghafoor Kulahmetov, Ahmethadi Maxudov and others. Kayum’s early professional development was highly shaped by the influence of a progressive and talented scientist and educator, Imam Ahmed bin al-Saghit Shirdani. It was Shirdani who challenged the young man’s natural curiosity and critical thinking.

Kayum quickly mastered the Turkish, Arabic and Persian languages. He also got acquainted with the humanistic traditions of the East, and the basics of Islamic philosophy and law while reading the books by al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, Ibn Rushd, and other great thinkers. Already at that time he began studying Russian and Russian culture, became interested in the works of Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov, met with the Russian intellectuals and Orthodox missionaries. Equipped with the knowledge of the Russian culture, the young man turned his attention to European sciences, and later in life this helped him in predicting trends in the national education policy.

In 1855, Kayum Nasyri started teaching future Christian clergymen, first, at the Kazan religious college, and later, at the Kazan Theological Seminary, where he tried to involve his students in studying Tatar history, culture and language. At that time it was extremely courageous for a Muslim, since the Kazan Tatars disapproved any type of cooperation among faithful Muslims and Orthodox believers in the field of public education. The fear of being forcefully baptized or spiritually turned to Christianity remained very strong and was one of the traditional old-fashioned Tatar prejudices. By the middle of the 19th century, the official policy of forcefully baptizing Tatars was abandoned, and since that time the government was mostly oriented towards either Muslims or voluntarily baptized Tatars who, permeated with the ideas of Orthodoxy, would pursue the policy of the Russian state among their countrymen [2].

The Russian ethnographer S. Chicherina described such people in the following way, "He speaks Russian with some difficulty, but he is still more successful in turning the population into Russian-oriented folks than a Russian teacher, who has a professional certificate, but does not speak Tatar" [8, p.74]. In an effort to preserve their religious and national identity, Tatars were extremely suspicious of their countrymen, who had friends among Russian officials and missionaries. Kayum Nasyri did not only promote the Russian language, but also lived and worked in the very heart of the missionary life – the Kazan Theological Seminary. He was also commissioned by Christian missionaries to make copies of Russian liturgical books. Kayum became friends with Nicholas Ilminsky, a well-known orientalist and educator, author of the officially approved “Christianization” of the non-Russian population who lived in the Middle Volga regions and other Russian locations. But Kayum Nasyri always remained a Muslim and had never had any desire of becoming a Christian. Although if he did, he would have had a free access to any Russian university, would become part of the Russian society, but he chose to remain different, what was called, at that time, alien. Caught between a rock and a hard place, he never succeeded to fully integrate into Russian society and at the same time he almost completely lost touch with his countrymen. This by itself brought a lot of drama into his life.

In other words, the young teacher became an outcast among the Tatars, who called him "Urys Kayum" (Russian Kayum), "Russian agent," "Satlyk" (traitor), or "missionary." His circle of communication was limited and consisted only of seminary instructors and students. In a tiny room in the attic of the Seminary building, he would sit up late at night over the oriental manuscripts, Russian and European literature, first sketches and drafts of his future works [3].

During this time he joined the Kazan University as an unattached student, and became actively involved in the work of the "Society of Archaeology, History and Ethnography," and finally was accepted as a member of this society in 1885. Studying at the Kazan University, he managed to establish close cooperation with the eminent scientists – historians N.G. Firsov and M.M. Khomyakov, orientalists N.F. Katanov and G.S. Sablukov, the latter was the first translator of Quran from Arabic into Russian.

In the 1870s, Nasyri entered the most important period of his life, it happened when the Russian government made a decision to integrate Muslim confessional education into the Russian public education system. As a minimum, every student in religious Tatar schools was required to study Russian, alongside which secular Russian-Tatar schools were established. Though the resistance of clergymen and Muslim population was strong and bitter, besides, there were not enough (if any) Tatar teachers who could teach Russian [2; 4].

Kayum Nasyri remained the only Muslim in Kazan, able to effectively work as a teacher in the newly formed Tatar schools. He had no doubts that ethnic Tatars who lived in Russia should study Russian history and culture, as well as the Russian language. In 1871, he enthusiastically took up the organization of such a school in the Tatar Zabulachnoy part of the city, first on Mokraya street, and then in the heart of the Old Tatar settlement, not far from the Marjani mosque. However, the level of resistance from the Tatar population was unbelievably strong, and unfortunately the Russian official support remained just “verbal” – no funding came from any sources. Nasyri had nothing else to do but to provide school supplies, students’ meals and textbooks together with the school rent himself, out of his known meager salary. Moreover, he had to pay students for their attendance, and even in this situation they would leave the building with every opportunity. Ministry officials also considered him too independent as he was not active enough in missionary work, and because of it he always had conflicts with the inspector of Tatar schools V.V. Radlov. Nasyri made everything possible to preserve his school, but in 1876 he was forced to close it.

The rest of his life was spent on serious research. During this period he wrote the most significant works in the field of Tatar linguistics, creating the fundamentals of the modern Tatar language, its grammar and syntax, morphology and phonetics; composed the first dictionary of the Tatar language, which played an important role in the development of Tatar scientific terminology. Kayum Nasyri made a significant contribution to the development of the Tatar literature, which under his influence started to move away from the canons of oriental poetry and became more focused on the West. While writing his works in Tatar, he tried to avoid borrowings from Arabic and Persian languages. He was also known as a brilliant interpreter of many wonderful novels and short stories from Arabic, Turkish and Persian languages [6].

Nasyri paid much attention to the study of local history and the history of the Tatar people, their folklore and ethnographic heritage. He was greatly respected in the scientific community of Kazan. The results of his ethnographic and historical research were always warmly received at the meetings of Kazan University Society of Archaeology and Ethnography. Starting from 1871 and for the next 27 years the educator would publish his annual calendar. In these calendars he introduced readers to the Tatar history and culture, in a way they served as literary encyclopedias. He wrote about various aspects of people’s lives and would touch upon different scientific achievements in the fields of history, geography, literature, linguistics, etc. Still today, the data collected in his calendars could serve as an important reference material for research, as there were reviews of books and textbooks, even recommendations in education and character formation were given. In other words, Nasyri can also be considered a pioneer of Tatar periodicals.

As an ardent supporter of Tatar-Russian friendship, he was the first educator to introduce Russian history and culture to Tatars in their native language, to translate many Russian geography, physics, mathematics and linguistics textbooks into his mother tongue. He was the originator of the Tatar-Russian dictionary, the author of the Russian grammar textbook for Tatars, as well as a creator of some popular works for a wider public.

Kayum Nasyri is often called "Tatar Lomonosov" for his encyclopedic knowledge. In fact, he wrote a number of works in literature, education, agriculture, botany, medicine, composed textbooks in arithmetic, geometry, and geography. The total selection of his writings is over forty volumes. The most famous among them are: "The book on education" (1881), "A brief history of Russia" (1890), and "The tale of Avicenna" (1872). During his whole life Nasyri was writing sermons and talks, which later became a volume under the title, "The fruits of our conversations", published at the Kazan University printing house in 1884. This volume accumulates the whole Tatar educational ideology, and until today it preserves a high educational and scientific value.

Nasyri was a man of many talents – he could bind books, make mirrors, prepare starch using electricity (galvanizing); he knew carpentry, cooking and traditional medicine. He criticized doctors when they were using imported drugs. He believed that local plants should be used as medications and that they had a number of healing properties, better than foreign ones. It is worth noting, that when Nasyri himself had a stroke, he did not ask for medical help. On the contrary, he developed special training exercises and performed them; he also treated himself with electricity and, as a result, recovered.

Kayum Nasyri served as a high example for young Tatar intelligentsia of the late 19th - early 20th century – G.Tukai, F. Amirkhan, G. Ibragimov, G. Kamal and others, who launched national literature, theatre, art and science. Nasyri’s multi-faceted activity and his works reflected the thoughts and aspirations of his native people and their joyless fate. His cherished dream was to rescue the Tatar nation out of stagnation, poverty, age-old backwardness, social and national oppression. In his works he tried to solve different problems from the point of view of the Enlightenment. He believed that anything could be overcome with the help of education and creation of national public schools. In this regard, he raised the question of the role of science in society, and preached the omnipotence of knowledge, truly considering that science was the most valuable human achievement. From his point of view science was a true source of knowledge, and knowledge constituted a necessary foundation of any human activity. Realizing that a world without education would be poor, Nasyri sought the most effective and innovative ways to provide the life of his people with the “products” of enlightenment and knowledge.

Nasyri’s views regarding moral and ethical issues impacted his understanding of education and teaching. In his opinion, to become a true rationale human being, a person should have an influence of both – education and his/her social surroundings. In this regard, he shared the same ideas as the thinkers of the Enlightenment of the 18th century.

Nasyri’s pedagogical views were developed under the influence of Konstantin Ushinsky and Leo Tolstoy. Following the ideas of these Russian educators, Nasyri believed that children should study their native language, live in the atmosphere of their own culture, preserve old traditions, love their home, their village or town and their Motherland, respect their neighbors, know their culture and their faith to escape misconceptions, and strive to the heights of modern science. That is how Nasyri understood the educational ideal of a person.

In a small volume "Book on education," containing instructions, instructive stories and parables, he raised many issues in the field of moral education. For example, he wrote, "Education should not be understood as worrying only about children’s nutrition and growth; education includes everything – nutrition, growth, moral development, and inculcation of the beautiful, noble manners. And it is also a desire to withdraw a child from a mere biological state of existence, and to make the child worthy of his/her human nature; it is also teaching sciences, and developing the child’s decency." This volume is a collection of wise rules, it serves as a pedagogical guidebook for the education of younger generations. Using examples from the life of sages and common people, Nasyri first describes the events and then draws the conclusions, leads the reader to the moral teachings that are not set out in the form of morals and doctrines, but presented in the form of everyday problems, straightforward advice, and strategies of behavior for the future [5].

The First Precept in Nasyri’s book is about education.

"A wise man taught his children: “Oh, dear children, take my advice – learn some craft. Property and money are so unreliable in this world. Gold and silver is a danger to the traveler. Craft is inexhaustible, as a wellspring. A craftsman will not know tribulations even if deprived of his wealth. Master handicrafts, learn decency."

The book also teaches the importance of etiquette. "Alexander the Great was asked, "How did you achieve obedience from the East and West? Former rulers spared neither troops nor treasure, but were not able to win so many countries." Alexander answered, "I would conquer the country, but not hurt its people. I commemorated former rulers only in a good way." Oh, my son, do you see how powerful a person with good manners could be? Kindness and gentleness are taking the city, you have to be kind and forgiving to all, beware to speak ill even of your enemies. "

Nasyri paid special attention to the healthy lifestyle and nutrition. He wrote, "We know that a Persian king sent one of his best doctors to the prophet in Arabia. This doctor lived there for a few years, but no one ever asked him for help. Then he went to the Prophet and complained, saying that though he lived there for years, people would not pay attention to him. The Prophet answered, "The people do not eat here, as long as they are not hungry, and they turn away from food before they feel full". "So that's why they never get sick,” said the physician, kissed the ground and left. I believe, my son, you have understood the meaning of this parable. Do not overeat, because it would ruin you health, and learn how to feel full with the little amount of food you have."

In conclusion, we will quote from a few precepts that form the moral basis of this book. For example, Precept 41. “Oh, my son, there are two groups of people whose lives are meaningless and useless. Some are saving during their whole lives and never use their savings. Others save up their knowledge, but never use it for their work. Be aware of these groups and try not to follow their examples.”

Precept 83. “Oh, my son, even though the truth could be bitter, never tell lies. If you want to keep a secret from the enemy, do not share it with your friend. Be respectful to elders and do not hurt younger ones. Avoid the ignorant and the slackers.»

In his old days the educator was paralyzed and died on August 20, 1902. He was buried by the students from the Madrassah "Muhammadia" in the Kazan Novotatarsky cemetery.

The memory of this outstanding educator has never faded away with time, more so in the recent history we can see it in the names of streets, memorial sites and museums, his works have been widely published and promoted. However, this posthumous fame and appreciation could serve as a small reward to the person who, while pursuing truth, constantly experienced his contemporaries’ misunderstanding and even hostility, poverty and failure, cold and gloomy loneliness.

References

1 Valeeva, Roza Alexeevna [In Russian: Роза Алексеевна Валеева], PhD, Professor of Education, Kazan Federal University, Kazan, Russia.

Home | Copyright © 2025, Russian-American Education Forum