Volume:2, Issue: 2

Aug. 1, 2010

Aug. 1, 2010

Foreword. At the end of the 1990s experimental educational sites became quite popular in Moscow. They served as tools for renewing and modernizing the city system of education. These experimental sites were part of a regional program of development entitled “Education in the Capital #1.” A number of prominent researchers who were anxious to support practitioners participated in its strategy-development (Nikita Alexeev, Yury Gromyko, Victor Slobodchikov a.o.) At present Moscow faces the fifth stage of this program (2009 - 2011). The main objective of experimental sites is to design, test, and implement such strategies, methods, and forms that increase the quality of education and challenge the teachers’ professional development, and as a result, help to improve educational management in Moscow in general.

Below you will find three articles that describe the activities of one of such experimental sites called “Pedagogical Design as a Factor in Planning for Early Childhood Learning Activities (in a preschool and in an elementary school.)” The articles are written by the head of this experimental site Dr. Lyubov Klarina and the preschool teachers who participated in the experimental work during the period from 2007 to 2010.

TITLE: Vital Skills for a Modern Preschool Educator

AUTHOR: Klarina, Lyubov M.1

DESCRIPTORS: kindergarten, preschool, early childhood education, teaching skills, school-family commonality or shared interest groups, problem identification and analysis, educational planning, project design, project implementation, educational reflection, educator and student self-development, anthropological approach to teaching, model projects, teacher training tools.

SYNOPSIS: In this article, Dr. Klarina lays out a thorough plan of action for teachers to use in solving their little or large educational problems that they face in their school setting on a daily basis. Employing an anthropological approach to problem solving that is holistic in its scope, Dr. Klarina provides a valuable outline for use in educational planning with a stress on reflection at all stages of the process. Her list of necessary skills and her perception of the role of the teacher as an educational leader are critical tools for any teacher preparing to begin an educational problem solving activity.

Vital Skills for a Modern Preschool Educator

INTRODUCTION

Contemporary life with its inherently constant changes in the economic, technical, scientific, social, and political spheres places enormous pressure on the entire field of education. Under these new conditions, it is necessary to reconstruct the field of education so as to give teachers the ability not only to survive and adapt to the changes that they are facing, but also to participate in establishing their own classroom situations, discerning for themselves what is necessary according to the changing circumstances, thereby promoting the development of original and progressive changes. The basic principle for education then is not so much the acquisition of knowledge as the development of the rising generation.

The leading goal of “developmental” education that is understood as the “special cultural-historical formation and development of talent” requires that the “student” learns to develop himself. He/she becomes the subject of his/her own development. Apparently, the best time to begin such education ought to be when the student is still of preschool age when the foundational base of the personality and culture of a person is still forming.

In order to accomplish these goals during the preschool years, it is necessary to create school conditions which promote in young children the formation and development of the abilities that foster self-realization, self-development, and vigorous interaction with the world. It is widely known that one of the key conditions for the development of children appears to be the formation of the personality. Behavior modeled by adults; the capacity to transfer life values, norms and rules to the child; as well as the cultural-historical experience accumulated by mankind bears a significant influence on the preschool child.

AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACH

What must preschool and kindergarten teachers do, then, to begin the development of the young children in their care in the proper direction?

We consider the aforementioned question from the position of an anthropological approach. This approach to the solution of pedagogical problems first appeared in Russia during the 19th century through the work of N. I. Pirogov and K.D. Ushinsckii. It was further developed in the psychological-anthropological conception of the objective reality of a person by S.L. Rubinstein and his disciples in the middle of the 20th century, but unfortunately, it was not possible to publish the greater part of their findings during the Soviet period. Only at the very end of the 20th century did the ideas of pedagogical anthropology again find importance, particularly, in the work of Victor I. Slobodchikov and like-minded people. At the center of attention for contemporary representatives of the pedagogical-anthropological philosophy is man, the creator of himself and his own life-path, the master, the author, the organizer, or in other words, the subject of his own destiny.

The leading goal of education from the point of view of the anthropological approach consists namely in the development of each child, his individual capabilities, his possibilities, and so on. He is definitely not to be cultivated by utilitarian preparation toward a fate in social reproduction in an economic sense, in order to fulfill instructions and programs handed down from above, or just to be taking orders from some functionary.

From the position of the anthropological approach, the teacher, is not simply the one who carries out, or executes the instructions of those in authority using the means and methods approved from on high, but the teacher must be the subject of his own professional work, and must define the goals and problems that relate to the training and education of those under his/her care, by seeking unorthodox paths to solving them. In order for these solutions to work effectively in real life, it is necessary that the teacher develop a plan/a project for any and every professional work.

The words “project” and “project-design” are heard more and more frequently nowadays. Some educators believe that this is all part of the latest fashionable campaign. For our purposes, “project” will be the key word. Several years back, use of this word began in the school-student environment, but since then “it has crossed over” into the pedagogical world. Like the effects of any fashionable campaign, this jargon quickly became obsolete, happily forgotten…

We, on the contrary, are thoroughly convinced that the ideas found in pedagogical planning and design should have a legitimate claim on our time both at present and in the future. The point is that without a plan or project, it is impossible to fully put into effect any newly discovered, creative, unconventional solution to an educational problem. Without fail, any other course of action would be negligent. Furthermore, in cases of unorthodox solutions, it is all the more necessary to painstakingly check, examine and verify whether anticipated outcomes were achieved and whether they brought along any unexpected consequences. In other words, introspection is necessary at all stages of working up and implementing an educational plan. Questions like the ones below are critical to successful implementation:

USING A PLAN

Therefore, the truly modern nursery school or kindergarten teacher has a detailed plan for each professional activity. Everything in the plan is in harmony with the thinking of planning expert N.G. Alexeyev and should follow his stages of plan development:

NECESSARY STAGES:

To make his outlined stages more relevant and specific to pedagogical activity, we suggest the following steps as a guide for pedagogical planning for “modern” teachers.

OUTLINE FOR PEDAGOGICAL PLANNING, IMPLEMENTATION, AND REFLECTION

The outline above has been rigorously tested and is approved by the City of Moscow’s Education Experimental Site: “Pedagogical Design as a Factor in Planning for Early Childhood Project-Learning Activities” which comprises a number of Moscow preschool establishments.

In the process of our work, we came to the conclusion that for the modern preschool or kindergarten teacher facing educational problems both big and small, it is first necessary for him/her to analyze existing conditions and take into account the diversity of its nuances. Apart from clarification of the didactic, social, natural, and objective/material conditions which have their own differences, such an analysis allows for the consideration and individual/personal distinctiveness of the character, interests, and abilities of a single child, groups of children, or even the pedagogy itself. All this is helpful in uncovering the real nature of problems, identifying necessary decisions, and clarifying causes of the appearance of the problem in the first place. Thanks to this type of analysis, it appears to be possible to develop a core concept for any pedagogical project.

The design takes the shape of the desired outcome intended by the author of the project:

Moreover, the design demonstrates “directional movement” toward the intended result:

We must make the point that, if one does not initiate an analysis of the situation, does not clearly identify the leading impediments to an expected solution, does not follow a plan which includes the organization of goals and tasks, one will not be in a position to direct the operation properly. In such cases where a coherent plan doesn’t exist, this is what happens: the team begins its task; it works on the assignment indefatigably; but the team does not know why it is doing what it is doing; the members don’t really understand why they are being asked to work this way or why they must do things that way. Failing to reveal the cause of their difficulty hinders their achieving the desired results; they venture “to search not there in the rough ground where the ball was lost, but over there, where the ground is clear” and the task is much more convenient!

It is not the team’s job to supply the goal of their project activity. That is the job of the author/organizer/leader of the project. However, if the team works without a well understood goal, they might eventually reach an end point, but the results of their work probably won’t be accurate and might provide only a mere sense of the cause of the original problem instead of a true solution. It is most important therefore that the author/organizer/leader must act thoughtfully, realize the needs of all participants, and provide all team members with a basic understanding of all aspects of the project.

Implementation of the plan then, necessitates, first, the construction of a community that will form the team of people who will strive for attainment of the envisioned results, and second, the completion of the program through the achievement of all of the plan’s goals. Next in the sequence of events required for successful implementation of the plan comes the series of active conditions and actual operations necessary to achieve a solution to the identified problem and thereby reach the goal of all of these tasks. Designers of the plan must select and embed in it a procedure that details the employment of the methods and resources that are vital to the plan’s successful operation. The detailed plan will provide important information to those who constitute the most valuable of all resources: the participants, the professionals, the temporary assistants, and so forth.

THE ROLE OF THE “SHARED INTEREST GROUP”

It should be noted that a pedagogical and/or educational plan in the nursery school or kindergarten setting or even in an elementary school, as a rule, has been found to be most successful when implemented not only by the individual teacher but by the entire professional-family commonality or professional-family shared interest group. (The Russian word “obshnost” is usually translated as commonality but for the purposes of the English language form of this article, the term, “shared interest group” or the initials “S.I.G.“ will be used.)

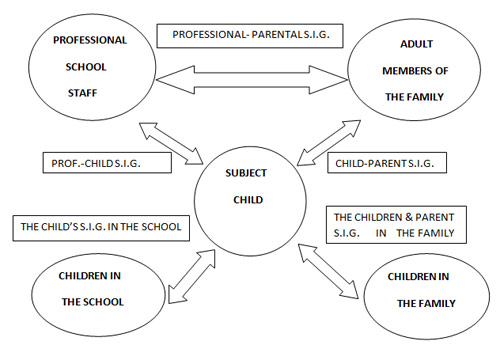

The “shared interest group” encompasses a wide variety of participants and has a very complex structure. (See the shared interest group diagram below.) It can involve aspects of the following:

Implementation of the educational project by the teacher in the nursery school or kindergarten frequently begins with the formation of “the professional-parental “shared interest group,’” that is the values-teaching “shared interest group” composed of teachers and parents of the pupils. Following this pedagogy, the authors of the project communicate the main ideas of the plan to the parents of the pupils in order to gain the greatest degree of cooperation from them during the implementation stage of the project. In these cases, it is necessary, first, to get an idea about the current understanding of the project and its goals from the point of view of the parents who will be participating. Who do they think is the focus of the project? What is the purpose of the project? What are the goals of the project? What should the goals of the project be? Can a solution resulting from the project be put into operation?

Reflection must be carried out at all stages of the project including during the design of the pedagogical plan, during the plan’s implementation, during the scrutiny of plan results, and during the review of the plan’s possible consequences. So, at the point of indicating and elaborating on reflection points during the design stage of the project, the following questions should be considered:

At the completion of the project it is necessary to reflect on answers to the following questions:

SHARED INTEREST GROUP DIAGRAM

The Family-Professional “Shared Interest Group”

SOME SAMPLE PROJECTS

During the spring of 2009, the first “Russian Festival of Pedagogical Projects” was held in Moscow. Educational institutions involved in our experimental program participated. More than 40 projects were represented. Children’s projects were also featured among the pedagogical frameworks presented. Included here is a small sample of projects presented at the 2009 Festival:

In general the content of these and other pedagogical projects that were presented at Festival 2009 confirm that most were successful and unearthed information that could be of use to the field of education. Moreover the subjective material proposed by the children was produced by means and methods that assisted the development of their own thinking and activities. Thanks to their participation, the children not only became more acquainted with the reality of their surroundings, but they also mastered new ways with which to interact with the world. This is extraordinarily important in helping a child become more independent. The student begins to recognize his ability to do things on his own including establishing his own “guidelines, rules, or laws” as in choosing from among a variety of possibilities the one best suited for solving each of the particular problems that he faces in his daily life or even modifying his “guidelines” or, perhaps better yet, devising entirely new ones.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we will briefly characterize several abilities and skills necessary for modern teachers of preschools and kindergartens so that these conscientious pedagogues may more efficiently and effectively employ an anthropological approach in planning and designing activities that meet the demands of the professional problems that they will face daily in their educational careers.

Analysis of the situation stage

The teacher must develop the ability to observe and analyze the daily interaction of child and parent and child with child. How can their individual behaviors be characterized? What qualities best describe them? What are interests do they manifest?

The teacher ought to ascertain by means of diagnosis the level of development of each of the children. How do they assimilate knowledge and master skills? How appropriate is their behavior? What is their ability to learn?

It is vital for the teacher to know how to identify and properly state problems that arise as well as recognize the “real” goal and consider the possible ways to attain it. The teacher must be familiar with a variety of instructional philosophies, methods, and pedagogical technologies. The modern teacher who wishes to be a skilled and wise educator must be open to the hard-earned experience of colleagues. Then once a problem is identified, the teacher can apply the necessary skills to select and analyze data regarding the problem and think critically while employing a solution.

Formation of the design stage

During the formation of the design stage, the teacher’s need to have independence to develop and defend his/her professional position takes on a special significance. At this time, it is necessary that he/she creates a personal identity: this individual must “know where he is going and who is going with him” (Ericson, E., Identity: Youth and Crisis, Moscow, 1996, p. 313, in Russian.)

Needs for the reflective stages

For conducting “pedagogical reflection” of the plan’s design and methods of implementation, the teacher will need an array of reflective abilities including: the skill to analyze one’s own values, interests, aptitudes, and peculiarities; the ability to pick out the negative and positive aspects of the design; the skill to record and analyze the results of one’s own activities and then compare them to the problems presented; the ability to predict the consequences or results of one’s actions.

The implementation stage

In order to put the planned design into motion, the teacher must possess the ability to plan the necessary activities. He/she must take “ownership” of the means and methods of this professional work, and must possess the ability to be flexible in applying them, and the fortitude to single-mindedly take whatever action is required. No less important are the organizational and communication skills required for the formation and development of the “professional-family shared interest group” necessary for implementation of this proposed educational project. Finally, as the educational leader of the project, he/she must possess the ability to understand the institution and the community that surrounds him/her, to have empathy for them, and be willing to contribute to them.

Role of the professional leader

Possessing all the necessary abilities outlined above, the preschool educator who is entering upon the process of solving an educational problem by means of the anthropological approach is now able to become the central figure, the author, the creator, the organizer of his/her own professional activity. This gives us hope that his/her students will grow up as the central figures of their own activities and their own development. By doing so, the teacher will take on his/her most rewarding task which is that of providing one’s students with the possibility of being the authors of their own destinies.

Home | Copyright © 2026, Russian-American Education Forum